Delicious Disappointment: Homemade Jam with Flawed Fruit

I used my day off on Friday to drive an hour to my favorite U-pick berry farm. And my morning was filled with disappointment. First, I found the owners had pulled out all the gooseberry and currant plants – which was my major motivation for visiting that specific farm. Second, I usually try to bring home a flat of raspberries, as it’s usually a couple hours’ of easy picking to fill all 8 quarts. Wrong again. After two hours of hunting for berries with the drive and dedication of the Swamp Fox looking for Redcoats (Is that red a ripe berry? No, dang it. The other side of it is orange), I managed two bare quarts, hoping for enough to make homemade jam. And many of the berries I did find were sporting significant damage.

In the time I spent picking, I acquired three new Babas – one Polish and two Czech – who tut-tutted over the lack of currants, patted my hand, and shook their heads over the lack of raspberries. Once I’d extracted myself, I stayed to pick 5 lbs of tart cherries – just to try to make the trip worthwhile.

So, what to do with 2 quarts of damaged raspberries? I didn’t really want to put them in the freezer – I’m not sure who they’d take it. But I could make homemade jam.

If you’ve ever read a modern jam recipe, you’ll notice the instructions will nearly without fail tell you to choose the best fruit, ripe but not over-ripe, and unblemished.

This is because, darlings, things like overripeness or bruising change the enzymes in the fruit. “Rotten” is simply the end stage of fruit, and “ripe” somewhere in the middle of the path. Fruit that has moved past perfectly ripe now has enzymes that can break down pectin.

Directions for jams and jellies that use purchased pectins are designed for fruit that falls within a specific sugar and pectin range. The developers of the recipes calculate what the average is for those fruits, factor in any lemon juice you are directed to add, and sugar, to determine a time in minutes for which the jam must be cooked. This entire system is designed to take all of the guesswork – and the ability to judge the setting point – out of jam-making. Easy-peasy-lemon-squeezie, right?

It also presupposes the ability to go to a store or market and purchase a specific quantity of perfect fruit. Most people possess an unreasonable expectation that fruit should be perfect in form, shape, color, and ripeness. Always. One of the first things that new gardeners discover is that not every piece of fruit or vegetable that comes off a plant is perfect. But that doesn’t make them less tasty, or less useful.

If, then, it is your purpose to grow your own fruit, you’ll be confronted by the dilemna that I had this weekend. What do you do?

First – assess the situation.

I have 2 quarts of raspberries, but jam made from them is going to be VERY seedy, due to the damaged portions on so many berries.

I also have 5 lbs of tart cherries.

Purchased pectin is still not available in stores near me – BUT, I did buy some early green apples at the Farmer’s Market on Saturday.

Hence – Cherry-Berry Jam. How?

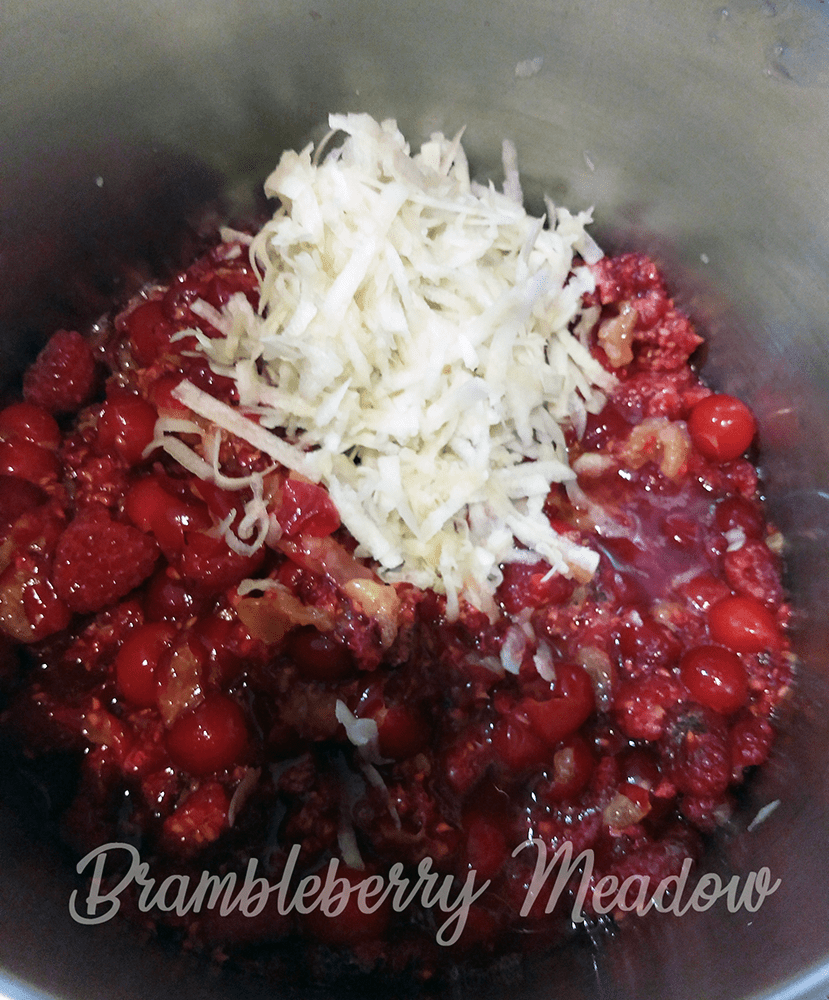

I put the raspberries in a large pot, with an equivalent quantity of pitted sour cherries. And then I peeled two of the apples, and grated them into the pot.

Trust me. I then cooked the fruit mixture until it the apples were translucent and it was bubbling nicely.

Now, I am normally not bothered by raspberry seeds in my jam. And I normally prefer not to fuss overmuch. But… these were some really seedy berries. So, I ran the whole mass through a food mill, and then through a coarse sieve. The resulting jam isn’t quite seedless, but it’s also not unpleasantly crunchy.

The resulting juice/pulp went back into the pan with 5 cups of sugar (and at that, the end product is pretty darned tart!). And cooked until the setting point was reached. I prefer to pot my jam up in 8 oz jars, which should be processed in a boiling water bath for 5 minutes, if you intend for them to be shelf stable.

It is important to make sure that you’re only canning high acid foods in a boiling water canner. However, it is NOT necessary to use only perfect fruit. Recognize what you DO have, and adjust your processes to compensate. Remember that the precision of most modern recipes hinge on the need to cook by time. You actually CAN adjust sugar levels to your liking, if you’re willing to rely on judging the jelling point rather than just setting a timer. Homemade jam, after all, existed before commercial pectin.

Breaking the mindset that produce has to look perfect is part of growing and preserving your own food. Homemade jam is an easy place to start. If you’re looking for fruit suitable for jam, you really should think about growing your own. I talked about unusual fruits for the farmstead on the podcast this week. Give it a listen!